Cock

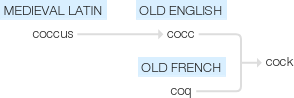

Old English cocc, from medieval Latin coccus ; reinforced in Middle English by Old French coq .

wiktionary

From Middle English cok, from Old English coc, cocc(“cock, male bird”), from Proto-West Germanic *kokk, from Proto-Germanic *kukkaz(“cock”), probably of onomatopoeic origin.

Cognate with Middle Dutch cocke(“cock, male bird”) and Old Norse kokkr("cock"; whence Danish kok(“cock”), dialectal Swedish kokk(“cock”)). Reinforced by Old French coc, also of imitative origin. The sense "penis" is attested since at least the 1610s, with the compound pillicock(“penis”) attested since 1325.

Uncertain. Some authors speculate it derives from cockle, a yonic fertility symbol, [1] others suggested it entered Southern US vernacular during the period of French rule (of Louisiana) from Cajun French coquille(“shell”) (itself the source of cockle), which in 18th and 19th century slang meant the vulva. [2]

From Middle English cokke, cock, cok, from Old English -cocc(attested in place names), from Old Norse kǫkkr(“lump”), from Proto-Germanic *kukkaz(“bulge, swelling”), from Proto-Indo-European *geugh-(“swelling”).

Cognate with Norwegian kok(“heap, lump”), Swedish koka(“a lump of earth”), German Kocke(“heap of hay, dunghill”), Middle Low German kogge(“wide, rounded ship”), Dutch kogel(“ball”), German Kugel(“ball, globe”).

from Middle English cok, from Old French coque(“a type of small boat”), from child-talk coco 'egg'

cock

etymonline

cock (n.1)

"male of the domestic fowl," from Old English cocc "male bird," Old French coc (12c., Modern French coq), Old Norse kokkr, all of echoic origin. Compare Albanian kokosh "cock," Greek kikkos, Sanskrit kukkuta, Malay kukuk. "Though at home in English and French, not the general name either in Teutonic or Romanic; the latter has derivatives of L. gallus, the former of OTeut. *hanon-" [OED]; compare hen.

Old English cocc was a nickname for "one who strutted like a cock," thus a common term in the Middle Ages for a pert boy, used of scullions, apprentices, servants, etc. It became a general term for "fellow, man, chap," especially in old cock (1630s). A common personal name till c. 1500, it was affixed to Christian names as a pet diminutive, as in Wilcox, Hitchcock, etc.

A cocker spaniel (1823) was trained to start woodcocks. Cock of the walk "overbearing fellow, head of a group by overcoming opponents" is from 1855 (cock in this sense is from 1540s). Cock-and-bull in reference to a fictitious narrative sold as true is first recorded 1620s, perhaps an allusion to Aesop's fables, with their incredible talking animals, or to a particular story, now forgotten. French has parallel expression coq-à-l'âne.

Cock-lobster "male lobster" is attested by 1757.

The cock-lobster is known by the narrow back-part of his tail; the two uppermost fins within his tail are stiff and hard, but those of the hen are soft, and the tail broader. The male, though generally smaller than the female, has the highest flavour in the body; his flesh is firmer, and the colour, when boiled, is redder. [Mrs. Charlotte Mason, "The Ladies' Assistant for Regulating and Supplying the Table," London, 1787]

cock (n.2)

in various mechanical senses, such as "turn-valve of a faucet" (early 15c.), of uncertain connection with cock (n.1). Perhaps all are based on real or fancied resemblances not now obvious; German has hahn "cock" in many of the same senses.

The cock of a firearm, which when released by the action of the trigger discharges the piece, is from 1560s. Hence "position into which the hammer is brought by being pulled back to the catch" (1745). For half-cocked, see cock (v.).

cock (v.)

mid-12c., cocken, "to fight;" 1570s, "to swagger;" 1640s as "to raise or draw back the hammer or cock of a gun or pistol as a preliminary to firing." Seeming contradictory modern senses of "to turn or stand up, turn to one side" (as in cock one's ear), c. 1600, and "to bend" (1898) are from the two cock nouns. The first is probably in reference to the posture of the bird's head or tail, the second to the firearm position.

To cock one's hat carries the notion of "defiant boastfulness." But a cocked hat(1670s) is merely one with a turned-up brim, such as military and naval officers wore on full dress occasions.

To go off half-cocked in the figurative sense "speak or act too hastily" (1833) is in allusion to firearms going off unexpectedly when supposedly secure; half-cocked in a literal sense "with the cock lifted to the first catch, at which position the trigger does not act" is recorded by 1750. In 1770 it was noted as a synonym for "drunk."

cock (n.3)

"penis," 1610s, but certainly older and suggested in word-play from at least 15c.; also compare pillicock "penis," attested from early 14c. (as pilkoc, found in an Anglo-Irish manuscript known as "The Kildare Lyrics," in a poem beginning "Elde makiþ me," complaining of the effects of old age: Y ne mai no more of loue done; Mi pilkoc pisseþ on mi schone), also attested from 12c. as a surname (Johanne Pilecoc, 1199: Hugonem Pillok, 1256; there is also an Agnes Pillock). Also compare Middle English fide-cok "penis" (late 15c.), from fid "a peg or plug."

The male of the domestic fowl (along with the bull) has been associated in many lands since ancient times with male vigor and especially the membrum virile, but the exact connection is not clear (the cock actually has no penis) unless it be his role as fertilizer of the domestic hens, and there may be some influence from cock (n.2) in the "tap" sense.

The slang word has led to an avoidance of cock in the literal sense via the euphemistic rooster. Murray, in the original OED entry (1893) called it "The current name among the people, but, pudoris causa, not admissible in polite speech or literature; in scientific language the Latin is used" (the Latin word is penis). Avoidance of it also may have helped haystack replace haycock and vane displace weather-cock. Louisa May Alcott's father, the reformer and educator Amos Bronson Alcott, was born Alcox, but changed his name.

Cock-teaser, cock-sucker emerge into print in 1891 in Farmer and Henley ("Slang and Its Analogues").