分类:风险态度的测量

研究背景和问题

著名的使用非常普遍的风险测量十项决定实验[1][2][3]用了十组二选一(被试从每一个A、B两个彩票选项中做出来选择A还是B)的彩票来度量被试的风险态度。每一对的均值和方差和下一对都不一样,但是,维持从上到下BA选项的均值的差在不断增加,同时B选项的波动性一直维持比A选项要大。详细见下表。

| Option A | Option B | Expected payoff difference | Variation difference | estimated range of [math]\displaystyle{ r }[/math][4] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1/10 of $2.00, 9/10 of $1.60 | 1/10 of $3.85, 9/10 of $0.10 | $1.17 | -1.25 | r<-1.71 |

| 2/10 of $2.00, 8/10 of $1.60 | 2/10 of $3.85, 8/10 of $0.10 | $0.83 | -2.22 | -1.71<r<-0.95 |

| 3/10 of $2.00, 7/10 of $1.60 | 3/10 of $3.85, 7/10 of $0.10 | $0.50 | -2.92 | -0.95<r<-0.49 |

| 4/10 of $2.00, 6/10 of $1.60 | 4/10 of $3.85, 6/10 of $0.10 | $0.16 | -3.34 | -0.49<r<-0.14 |

| 5/10 of $2.00, 5/10 of $1.60 | 5/10 of $3.85, 5/10 of $0.10 | -$0.18 | -3.48 | -0.14<r<0.15 |

| 6/10 of $2.00, 4/10 of $1.60 | 6/10 of $3.85, 4/10 of $0.10 | -$0.51 | -3.34 | 0.15<r<0.41 |

| 7/10 of $2.00, 3/10 of $1.60 | 7/10 of $3.85, 3/10 of $0.10 | -$0.85 | -2.92 | 0.41<r<0.68 |

| 8/10 of $2.00, 2/10 of $1.60 | 8/10 of $3.85, 2/10 of $0.10 | -$1.18 | -2.22 | 0.68<r<0.97 |

| 9/10 of $2.00, 1/10 of $1.60 | 9/10 of $3.85, 1/10 of $0.10 | -$1.52 | -1.25 | 0.97<r<1.37 |

| 10/10 of $2.00, 0/10 of $1.60 | 10/10 of $3.85, 0/10 of $0.10 | -$1.85 | 0 | 1.37<r |

对于风险中性的人来说,其只关心A、B两个选项均值的对比。这样的话,肯定是在前几次中选择A在后面几次中选择B。例如在第五次开始转变。对于风险厌恶的人来说,有可能就算在B选项可能获得更高的均值的情况下,由于可能方差也大,或者直接看可能获得的钱也可以B选项可能获得的收益的了解比A的更加弥散,于是倾向于选择更加保守的A选项。反过来,对于风险喜爱的人来说,就有可能更加追求弥散的分布来,于是更早的选择B。于是,从第几轮开始选择B就成了一个风险态度的度量。

但是,这个有一个问题。这样测量出来的风险态度是把对均值更大的追求和对方差更大或者更小(或者说分布函数更加集中还是弥散)的追求合在一起的。有没有一个办法把追求均值和追求方差更大还是更小区分开来呢?

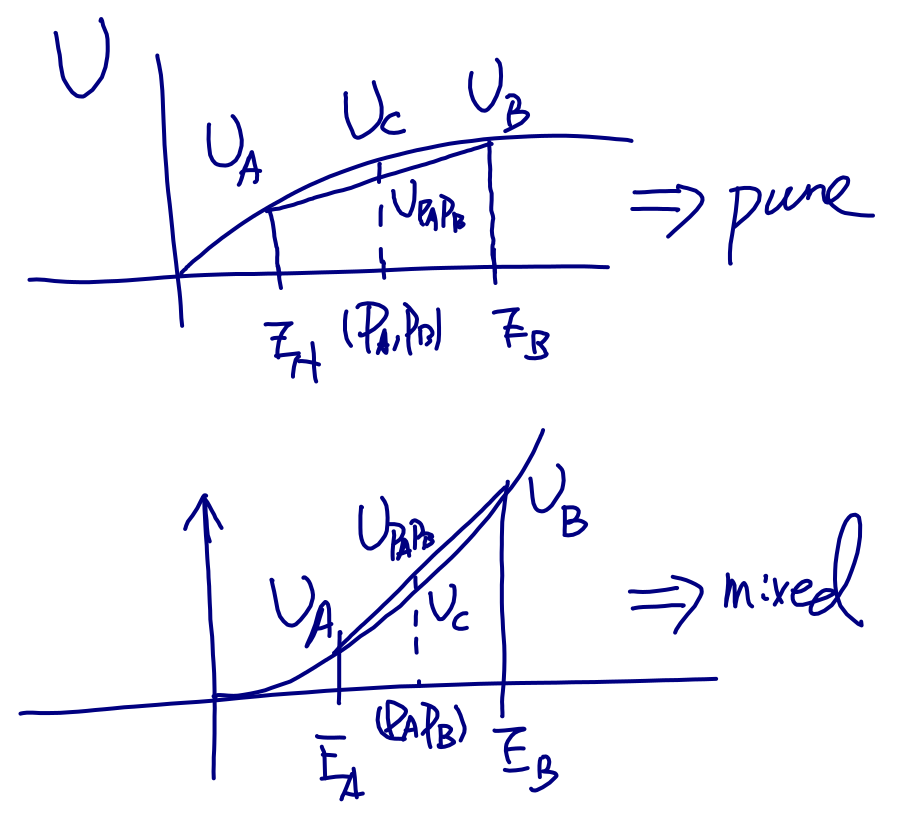

这个时候,就可以考虑对比两个均值一样但是方差不相同的选项,被试选择哪一个来测量被试是纯粹风险厌恶或者纯粹风险喜爱。还可以考虑两个方差一样但是均值不相同的选项,被试选择哪一个来测量被试是理性的有计算和理解能力的或者是由于某些原因(例如计算能力、理解能力)而造成的非理性的。当然,这其中还牵涉到一个就算能够理解和计算,但是不一定能够用于问题解决的因素,见知道到运用的距离。

前者这样的A、B选项很容易构造出来。后者实际上,概率匹配问题就是这样的A、B选项问题——方差一样,均值不同。

在这个研究中,我们就想看看,能不能在这个典型风险态度的测量实验的基础上,加上或者替换一些选项[5],能够把这样的纯风险厌恶或者喜爱程度、纯收益理性程度,也能够测量出来。

十项决定中风险测量的理论基础

期望效用理论[6],带有风险的效用理论[7],或者修改以后得到的前景理论(Kahneman and Tversky,1979[8]), 等级依赖期望效用理论(Quiggin, 1982[9]), 累积前景理论(Tversky and Kahneman,1992[10]), 前景理论与传统理论的综合模型( Bowman et al.,1999[11]; Köszegi and Rabin, 2006[12]),以及第三代前景理论(Schmidt et al., 2008[13])等[14],是这个十项决定的风险系数计算的理论基础。期望效用理论的意思就是如果有两个选择A、B,各自得到的效用是[math]\displaystyle{ U\left(A\right) }[/math]、[math]\displaystyle{ U\left(B\right) }[/math],则以一定的概率[math]\displaystyle{ P_{A} }[/math]、[math]\displaystyle{ P_{B} }[/math]实现这两个选项得到的合起来的收益就是[math]\displaystyle{ U=P_{A}U\left(A\right)+P_{B}U\left(B\right) }[/math]。在这个假设下,风险中性就可以这样来看,[math]\displaystyle{ U^{rn}\left(A\right)=\beta E\left(A\right) }[/math],其中[math]\displaystyle{ E\left(A\right) }[/math]就是选项[math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math]的货币形式的收益。也就是说,风险中性的决策者仅仅关注货币收益的平均值[math]\displaystyle{ U=\beta\left(P_{A}E\left(A\right)+P_{B}E\left(B\right)\right) }[/math]。如果是风险厌恶的决策者,则[math]\displaystyle{ U^{ra}\left(A\right) \lt U^{rn}\left(A\right)=\beta E\left(A\right) }[/math],也就是说具有不确定性的时候,A、B混合选项的平均收益要小于它们的货币形式的平均收益。对于风险爱好者,则正好相反,[math]\displaystyle{ U^{rs}\left(A\right) \gt \beta E\left(A\right) }[/math]。为了简化记号,以下采用[math]\displaystyle{ \beta=1 }[/math]。

这样的效用函数有一个很好的推论。我们来考虑:如果我们拿一个确定性的能够获得一份收益[math]\displaystyle{ E\left(C\right) }[/math]的选择,来和一个随机性的能够获得一个平均收益相同[math]\displaystyle{ P_{A}E\left(A\right)+P_{B}E\left(B\right)=E\left(C\right) }[/math]的选项来换,我们选择哪一个?如果是风险中性的,则两个选择完全等价。如果是风险厌恶的,则[math]\displaystyle{ U^{ra}\left(A, B\right) \lt U^{rn}\left(A,B\right)=P_{A}E\left(A\right)+P_{B}E\left(B\right)=E\left(C\right)=U\left(C\right) }[/math]。因此,选择选项C。如果是风险爱好的,则[math]\displaystyle{ U^{ra}\left(A, B\right) \gt U^{rn}\left(A,B\right)=P_{A}E\left(A\right)+P_{B}E\left(B\right)=E\left(C\right)=U\left(C\right) }[/math]。因此,选择选项(A,B)混合。

因此,这个“期望效用”理论——混合选项的效用是各自效用之和,风险态度不同的人的纯选项的效用函数绝对值不同——看起来是有合理之处的。 或者更一般的前景理论,[math]\displaystyle{ U^{PT}\left(A,P_{A};B, P_{B}\right)=W\left(P_{A}\right)U\left(A\right)+W\left(P_{B}\right)U\left(B\right) }[/math],或者稍微狭窄一点的前景理论,[math]\displaystyle{ U^{PT}\left(A,P_{A};B, P_{B}\right)=W\left(P_{A}\right)E\left(A\right)+W\left(P_{B}\right)E\left(B\right) }[/math]。两者的区别是,前者在概率和货币收益上都允许主观评价的存在,而后者仅仅在概率上有主观感受的存在,在货币收益上,没有主观评价的存在。通常所说的前景理论指的是前者[15]。

一般的[math]\displaystyle{ U^{PT}\left(A,P_{A};B, P_{B}\right)=W\left(P_{A}\right)U\left(A\right)+W\left(P_{B}\right)U\left(B\right) }[/math],其中[math]\displaystyle{ W\left(P\right) }[/math]和[math]\displaystyle{ U\left(E\right) }[/math]都是非线性函数,被称为前景理论。如果[math]\displaystyle{ W\left(P\right)=P }[/math],[math]\displaystyle{ U\left(E\right) }[/math]非线性,则被称为期望效用理论。如果[math]\displaystyle{ W\left(P\right) }[/math]非线性,[math]\displaystyle{ U\left(E\right)=E }[/math],则我称之为前景收益理论。如果[math]\displaystyle{ W\left(P\right)=P }[/math],[math]\displaystyle{ U\left(E\right)=E }[/math],则被称为期望收益理论。

纯粹的基于效用函数的形式的研究

在大量的研究里面,纯粹基于效用函数的形式(函数自身、函数的各阶导数)的研究占有重要分量。例如,当效用函数是收益的线性函数的时候[math]\displaystyle{ U\left(E\right)=E }[/math],二阶以及以上的导数为零。于是,我们发现,[math]\displaystyle{ U\left(A,P_{A};B, P_{B}\right)=W\left(P_{A}\right)E\left(A\right)+W\left(P_{B}\right)E\left(B\right) }[/math]。这个时候,我们发现,决策者必然是风险中性的:考虑一个确定收益[math]\displaystyle{ E_{C}=W\left(P_{A}\right)E\left(A\right)+W\left(P_{B}\right)E\left(B\right) }[/math]正好就是随机策略的收益的线性组合(混合),我们问,这个决策者,会选择纯策略还是混合策略?显然,两者正好相等,因此,这样的决策者正好就是风险中性的。

接着我们想看看什么样的收益函数,会是风险厌恶或者风险喜好的决策者。为了简单记,我们先试试这样的函数[math]\displaystyle{ U\left(E\right)=E^{\alpha} }[/math],其中[math]\displaystyle{ \alpha }[/math]大于(小于)1的时候表示边际效用递增(递减),甚至我们可以计算出来更高阶的导数。现在,我们来看,面对混合策略[math]\displaystyle{ U\left(A,P_{A};B, P_{B}\right)=W\left(P_{A}\right)U\left(E\left(A\right)\right)+W\left(P_{B}\right)U\left(E\left(B\right)\right) }[/math]和纯策略[math]\displaystyle{ U\left(C\right)=U\left(W\left(P_{A}\right)E\left(A\right)+W\left(P_{B}\right)E\left(B\right)\right) }[/math],到底随着[math]\displaystyle{ \alpha }[/math]的值的不同,选取混合还是纯策略?这时候我们只要去对比混合策略和纯策略收益。具体算起来稍微比较复杂,但是利用图形非常好判断——函数的凹凸性也就是二阶导数决定了到底决策者厌恶还是喜好混合策略,就算在两者的均值一样的情况下。

顺着这个思路,人们还可以研究效用函数的高阶矩的在决策上体现出来的思考,以及在实际决策实验中是否会影响决策。

这个理论的问题

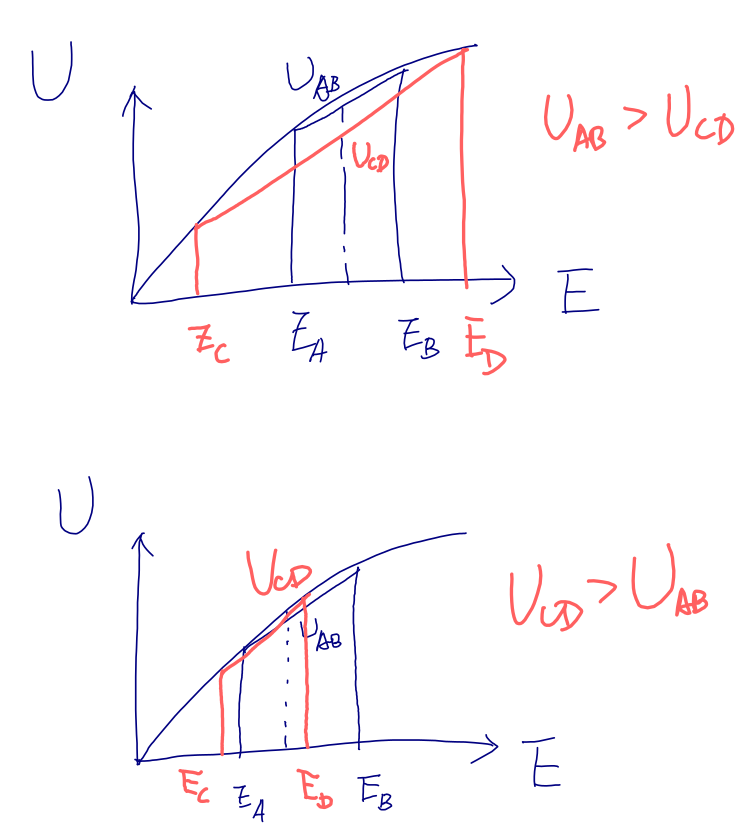

看起来这个理论似乎很有道理,但是,只要我们考虑两种混合策略的对比,则这个理论就失效了。我们来对比[math]\displaystyle{ U\left(A,P_{A};B, P_{B}\right)=W\left(P_{A}\right)U\left(E\left(A\right)\right)+W\left(P_{B}\right)U\left(E\left(B\right)\right) }[/math]和[math]\displaystyle{ U\left(C,P_{C};D, P_{D}\right)=W\left(P_{C}\right)U\left(E\left(C\right)\right)+W\left(P_{D}\right)U\left(E\left(D\right)\right) }[/math]就会发现,除了[math]\displaystyle{ \alpha }[/math],这个对比的结果依赖于更多的细节,例如概率的具体取值、[math]\displaystyle{ U\left(A\right), U\left(B\right) }[/math]是把[math]\displaystyle{ U\left(C\right), U\left(D\right) }[/math]包含在里面,还是有交叉等等各种情况。当然,原则上,这个不足仅仅表明凹凸性不再足够来决定系统的行为了,但是我们仍然可以继续考虑效用函数的高阶矩来建立行为和高阶矩之间的对应关系。

不过,这样的道路实在是太过复杂了。对于包含如此复杂的参数的效用函数,是不是能够通过行为把效用函数估计出来,然后用于解释实践,实在是没有太大希望。因此,不如反过来,直接对比策略之间的差别:均值的差别、方差的差别、三阶矩的差别、四阶矩的差别等等等等。这就是我们下面所要采取的道路。

均值方差研究思路

Markowitz[16]-Tobin[17]的均值方差(mean-variance, MV)理论是另一研究风险的路径。

Levy和Levy[18]对前景理论与均值方差理论的结合进行了研究。

更深刻的动机

更进一步,为什么想度量出来纯风险厌恶或者喜爱程度、纯收益理性程度呢?

为了将来构建一个综合考虑了收益(均值)和风险(方差或者弥散程度的某种度量)的效用函数,以及一个基于这个效用函数的决策模型。另外,为了这个目的,我们还需要研究一下,风险用什么样的方式进入效用函数——是否用方差来代表是可以的。例如,我们可以让选项A、B的均值方差都一样,但是更高阶矩不同,然后做多次来看被试的选择是不是具有稳定的方向性——例如追求更高或者更低的高阶矩。

为了符号简单,我们先假设只有两个可能的事件和相对应的收益,[math]\displaystyle{ X^{1}, X^{2} }[/math]和概率[math]\displaystyle{ P_{1}, P_{2} }[/math]。我们还假设对于决策者[math]\displaystyle{ \mu }[/math]来说,这个两个收益分别对应着绝对效用[math]\displaystyle{ U\left(X^{1}\right), U\left(X^{2}\right) }[/math]。现在,我们来做一个变换[math]\displaystyle{ \hat{X}=X-X^{1} }[/math],[math]\displaystyle{ \hat{U}\left(\hat{X}\right)=U\left(\hat{X}+X^{1}\right)-U\left(X^{1}\right) }[/math]。在这个新的变量的表示下,我们有[math]\displaystyle{ \hat{U}\left(\hat{X}=0\right)=0, \hat{U}\left(\hat{X}=X^{2}-X^{1}\right)=U\left(X^{2}\right)-U\left(X^{1}\right) }[/math]。以后,对于给定的情形,我们总是可以从原始的收益和效用开始,变成满足[math]\displaystyle{ \hat{U}\left(0\right)=0 }[/math]的效用函数。当然,要注意,这个变换在不同的实验之间是不能等同的,依赖于绝对变量[math]\displaystyle{ X^{1}, U\left(X^{1}\right) }[/math]。

- 一般地来说,对于一个混合决策[math]\displaystyle{ \rho }[/math],例如[math]\displaystyle{ \rho=P_{1}\left|X^{1}\right\rangle\left\langle X^{1}\right|+P_{2}\left|X^{2}\right\rangle\left\langle X^{2}\right| }[/math],我们可以算出开这个混合测略的均值、方差、高阶矩等等,或者至少,效用是这个混合测略的函数,[math]\displaystyle{ U=U\left(\rho\right) }[/math]。由于分布函数和一个分布函数的各阶矩的集合是等价的,因此,上面的函数也就可以写成[math]\displaystyle{ U=U\left(E\left(\rho\right),\Delta\left(\rho\right),\eta\left(\rho\right),\cdots \right) }[/math]。

- 有一种基于期望和效用的理论,可能可以提供概率决策的另一个描述框架:[math]\displaystyle{ U=U\left(\rho\right)=W\left(P_{1}, X^{1}, X^{2}\right)U\left(X^{1}\right)+W\left(P_{2}, X^{2}, X^{1}\right)U\left(X^{2}\right) }[/math]。

- 在特殊情况下,例如数学期望理论,[math]\displaystyle{ U=P_{1}X^{1}+P_{2}X^{2} }[/math]。在变换以后的变量下面,[math]\displaystyle{ U=P_{2}X^{2} }[/math]。

- 在期望效用理论下,[math]\displaystyle{ U=P_{1}U\left(X^{1}\right)+P_{2}U\left(X^{2}\right) }[/math]。在变换以后的变量下面,[math]\displaystyle{ U=P_{2}U\left(X^{2}\right) }[/math]。

- 在前景理论下,[math]\displaystyle{ U=W\left(P_{1}\right)U\left(X^{1}\right)+W\left(P_{2}\right)U\left(X^{2}\right) }[/math]。在变换以后的变量下面,[math]\displaystyle{ U=W\left(P_{2}\right)U\left(X^{2}\right) }[/math]。

- 在考虑了gain和loss的区别的前景理论下,[math]\displaystyle{ U=W\left(P_{1}, X^{1}-X^{2}\right)U\left(X^{1}\right)+W\left(P_{2}, X^{2}-X^{1}\right)U\left(X^{2}\right) }[/math]。在变换以后的变量下面,[math]\displaystyle{ U=W\left(P_{2}, X^{2}\right)U\left(X^{2}\right) }[/math]。

- 如果概率的数值不是明确给出来的,而是需要被是估计的,则一般的效用函数形式是,[math]\displaystyle{ U=U\left(m\left(\rho\right)\right)=W\left(m\left(P_{1}, X^{1}, X^{2}\right), X^{1}, X^{2}\right)U\left(X^{1}\right)+W\left(m\left(P_{2}, X^{1}, X^{2}\right), X^{2}, X^{1}\right)U\left(X^{2}\right) }[/math]。在考虑了gain和loss的区别的前景理论下,并且在做了变换的坐标下,[math]\displaystyle{ U=W\left(m\left(P_{2}, X^{2}\right), X^{2}\right)U\left(X^{2}\right) }[/math]。

这项研究的根本任务就是找出来,上面的每一种情形下的理论(见中间列表的四个理论形式)哪一个更好地描述了概率决策,并且如果可能的话给出来[math]\displaystyle{ W, U }[/math]具体的函数形式。例如,下面要讨论的模糊的研究则关注[math]\displaystyle{ m\left(P_{2}, X^{2}\right) }[/math]性质和具体的函数形式,而齐天笑的风险态度的度量和概率决策的研究,则是关注[math]\displaystyle{ U=U\left(E\left(\rho\right),\Delta\left(\rho\right),\eta\left(\rho\right),\cdots \right) }[/math]的函数形式和[math]\displaystyle{ U=W\left(P_{2}, X^{2}\right)U\left(X^{2}\right) }[/math]的函数形式。

例如,如果我们通过彩票选择实验或者其他实验来找到[math]\displaystyle{ m\left(P_{2}, X^{2}\right) }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ W\left(m\left(P_{2}, X^{2}\right), X^{2}\right) }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ W\left(P_{2}, X^{2}\right) }[/math]在某些给定[math]\displaystyle{ P_{2}, X^{2} }[/math]的条件下的值的话,我们就可能可以反推出来这些函数的形式,或者至少研究一下,是否有[math]\displaystyle{ m\left(P_{i}, X^{2}\right)+m\left(P_{j}, X^{2}\right)=m\left(P_{i}+P_{j}, X^{2}\right) }[/math]这样的性质。

上面的讨论用了两个事件的情形当例子,当是三个或者多个事件的时候,理论形式上类似,但是,问题的解决可能会复杂很多。这个从两事件到多事件(也就是从两选项的彩票变成三选项的彩票)是需要进一步研究的事情。

其次,如果实验中需要用到多次实验,则,还会出现“概率匹配”的现象——被试会主观上尝试避免掉进同一个坑里面而实际上客观独立事件的概率已经发生的事情不影响后面的事情。这也是需要考虑的事情。

甚至,对于明确给定的概率,有可能实际上还是存在着被试来估计这些给定的概率的一步——被试可以不相信实验设置尤其是语言描述的实验设置。这个时候,可以分别考虑用物理仪器和语言来描述实验设置的概率,来看结果的对比。从这个角度来说,实际上,对于明确给定概率的情形,也可以看作中间需要有概率估计这一步,并且来检验一下[math]\displaystyle{ m\left(P_{i}, X^{2}\right)+m\left(P_{j}, X^{2}\right)=m\left(P_{i}+P_{j}, X^{2}\right) }[/math]。

当然,被试能否理论上来计算概率和、能否计算期望,也都是需要区分和检验的。

两个理论基础的结合

现在如何把期望效用理论和分布函数的函数(其实是泛函)的数学形式相结合,以及从各阶矩的函数的角度来检验一下,到底函数形式如何,或者至少有哪些变量?这是一个有深远意义的问题。

广义地来看,如果我们允许分布函数的泛函包含货币收益的线性和非线性函数当作效用,则实际上,我们的框架包含了期望收益理论——期望收益相当于仅仅考虑一阶矩[math]\displaystyle{ U\left(\rho\right)=P_{A}E\left(A\right)+P_{B}E\left(B\right) }[/math]和期望效用理论,也就是[math]\displaystyle{ U\left(\rho\right)=P_{A}U\left(E\left(A\right)\right)+P_{B}U\left(E\left(B\right)\right) }[/math]。因此,分布函数的泛函的讨论是更加基本的问题。

同时,许彬等人的预实验发现,风险态度——假设可以用一个参数[math]\displaystyle{ \theta }[/math]来描述的话,受到被试的认知负担的影响。因此,实际上,我们是在做关于[math]\displaystyle{ U=U\left(\left. E\left(\rho\right),\Delta\left(\rho\right),\eta\left(\rho\right),\cdots \right|\theta\right) }[/math],或者说[math]\displaystyle{ U=U\left(\left. \rho \right|\theta\right) }[/math]的函数形式的研究。

另一方面,实际上,在期望效用理论的框架下面,方差是可以进入效用函数的:只要纯策略效用函数[math]\displaystyle{ U\left(E\right) }[/math]采用合适的非线性形式。例如使得随着收益的增加量递减。这样收益方差大的策略组合相比收益方差小的就会有比较低的效用,就算两组组合的收益均值一样。那么,是不是更高阶的矩也可以通过调整纯策略效用函数形式来包含到期望效用理论框架里面呢?

不过,无论如何,期望效用理论,甚至更一般的前景效用理论,和我们的泛函形式的效用理论,是可以同时展开研究的。相互不冲突。我们先来搞清楚泛函形式的效用理论里面有哪些自变量。

实验设计

这个实验研究的主要工作就是看看增加或者替换为什么样的选项,能够在测量出来风险态度的基础上,还能够测量出来纯风险厌恶或者喜爱程度、纯收益理性程度。

例如可以加入:

- 均值一样方差(分布函数弥散程度)不同的A、B选项,来看被试的选择

- 方差一样,均值不同的A、B选项,来看被试的选择

- 通过物理仪器给出来的明确的概率、语言描述给出来的明确的概率、自然事件给出来的需要估计的不明确但是存在的概率,来检验[math]\displaystyle{ m\left(P_{i}, X^{2}\right)+m\left(P_{j}, X^{2}\right)=m\left(P_{i}+P_{j}, X^{2}\right) }[/math],也就是定义和检验[math]\displaystyle{ \Delta_{ij}=m\left(P_{i}, X^{2}\right)+m\left(P_{j}, X^{2}\right)-m\left(P_{i}+P_{j}, X^{2}\right) }[/math]。

下一步的工作

- 文献调研,看看更多的风险态度测量的文章,以及风险态度在其他实验中对结果的影响的文献

- 预实验,尝试多种选项调整的设计

- 实验

不给定概率引起的风险态度

对于给定的概率,在期望效用理论的框架下,最一般的效用函数就是,前景理论:[math]\displaystyle{ U^{PT}\left(A,P_{A};B, P_{B}\right)=W\left(P_{A}\right)U\left(A\right)+W\left(P_{B}\right)U\left(B\right) }[/math]。当然,[math]\displaystyle{ W\left(P_{A}\right)+W\left(P_{B}\right) }[/math]可以等于、大于或者小于1。其中[math]\displaystyle{ W\left(P_{A}\right), W\left(P_{B}\right) }[/math]被称为主观感受概率。

前面,我们已经对这个带有主观感受概率的期望效用理论提出了挑战。现在,让我们来看另一个方面对这个理论的挑战或者说修正。

我们来考虑没有给出来概率[math]\displaystyle{ P_{A}, P_{B} }[/math],但是,假设有[math]\displaystyle{ P_{A}, P_{B} }[/math]存在的情境下的效用函数(主观期望效用理论[19])。比如说,我给你一个盒子红球和黑球,但是,我不告诉你各自多少个[20]。然后,让你来做一个跟红球和黑球概率相关的决策问题。例如问,你来做一个猜测一个颜色,我来取一个球,如果颜色对上了你就赢钱。问你怎么猜。这个时候,实际上,你需要产生一个对这个已经存在但是未知的概率的一个估计。为了和上面的给定概率情况下,决策者感受到的概率区别开了,我称这个主观对已经存在但是未知的概率的估计为主观估计概率,或者简称估计概率。

问:一旦有了估计概率的参与,效用函数怎么写?

我们假设,还是这样写:[math]\displaystyle{ U^{EPT}\left(A,E\left(P_{A}\right);B,E\left(P_{B}\right)\right)=W\left(E\left(P_{A}\right)\right)U\left(A\right)+W\left(E\left(P_{B}\right)\right)U\left(B\right) }[/math],或者把主观感受和主观估计合在一起记为函数[math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{E} }[/math],就是[math]\displaystyle{ U^{EPT}\left(A,E\left(P_{A}\right);B,E\left(P_{B}\right)\right)=\mathcal{E}\left(P_{A}\right)U\left(A\right)+\mathcal{E}\left(P_{B}\right)U\left(B\right) }[/math]。

为了对函数[math]\displaystyle{ W, U }[/math]了解更多,现在,我们来检验下面的事情,[math]\displaystyle{ W\left(E\left(P_{A}\right)\right)+W\left(E\left(P_{B}\right)\right){\overset{?}{=}}1 }[/math],以及,[math]\displaystyle{ E\left(P_{A}\right)+E\left(P_{B}\right){\overset{?}{=}}1 }[/math]。

为了简单,我们可以先假设主观感受函数[math]\displaystyle{ W\left(x\right)=x }[/math]。记住这是假设,将来要回来处理的。在这个假设下,我们前面两个需要检验的事情就成了一个,也就是,[math]\displaystyle{ E\left(P_{A}\right)+E\left(P_{B}\right){\overset{?}{=}}1 }[/math]。这个时候,我们就必须从实际决策实验中把[math]\displaystyle{ E\left(P_{A}\right), E\left(P_{B}\right) }[/math]推断出来,然后,才能来检验。可是,这个推断依赖于[math]\displaystyle{ E\left(A\right), E\left(B\right) }[/math],而这些是确定性决策——不考虑概率——的时候的效用。因此,如果想真的把[math]\displaystyle{ E\left(P_{A}\right), E\left(P_{B}\right) }[/math]推断出来,必须先知道[math]\displaystyle{ U\left(A\right), U\left(B\right) }[/math]。

估计概率是否归一和风险态度的关系

考虑前面红球黑球的例子,对于一个风险乐观的人来说,可能其估计概率之和会大于1:也就是说,会高估自己赢的可能,在猜中红球算赢的时候,觉得红球的几率大,而在猜中黑球算赢的时候,觉得黑球的几率大。这个实验很容易设计。例如,给定一个盒子的红球和黑球,不知道两种球的个数配置,第一组实验让被试在猜中红球算赢从而获得一笔钱Q(否则获得钱0)和以一定的概率赢同样数量的钱之间做选择;第二组实验让被试在猜中黑球算赢从而获得一笔钱和以一定的概率赢同样数量的钱之间做选择。分别找出来等价的几率,然后来看这个几率是否相加等于1。顺便,如果我自己来做这个实验,则,两者之和大概大于1——我总是把半瓶水看做已经有半瓶而不是才是半瓶。对于风险悲观的人来说,有可能就会把两者之和看做小于1——半瓶水总看做才半瓶而不是已经有半瓶了。因此,不仅仅要检验估计概率的归一性,还要看这个归一性和风险态度的联系。

也就是说,第一个实验,找找一个概率,使得, [math]\displaystyle{ U^{EP}\left(Q,E\left(P_{Red}\right);0,E\left(P_{Black}\right)\right)=E\left(P_{Red}\right)U\left(Q\right)+E\left(P_{Black}\right)U\left(0\right)=U^{EP}\left(Q,P_{1}^{*};0,1-P_{1}^{*}\right)=P_{1}^{*}U\left(Q\right)+\left(1-P_{1}^{*}\right)U\left(0\right) }[/math]。 在这里,如果[math]\displaystyle{ U\left(0\right)=0 }[/math],则我们得到[math]\displaystyle{ E\left(P_{Red}\right)=P_{1}^{*} }[/math]。否则,我们得不到这个简单的等式。按照我们之前讨论的变换——注意不同实验之间这样的变换不能通用,实际上,是能够做到[math]\displaystyle{ U\left(0\right)=0 }[/math]的。

我们再来第二个实验,找一个概率,使得 [math]\displaystyle{ U^{EP}\left(0,E\left(P_{Red}\right);Q,E\left(P_{Black}\right)\right)=E\left(P_{Red}\right)U\left(0\right)+E\left(P_{Black}\right)U\left(Q\right)=U^{EP}\left(Q,P_{2}^{*};0,1-P_{2}^{*}\right)=P_{2}^{*}U\left(Q\right)+\left(1-P_{2}^{*}\right)U\left(0\right) }[/math]。 同样,在这里,如果[math]\displaystyle{ U\left(0\right)=0 }[/math],则我们得到[math]\displaystyle{ E\left(P_{Black}\right)=P_{2}^{*} }[/math]。否则,我们得不到这个简单的等式。

如果我们得到了简单的等式,则我们只需要检验,是否[math]\displaystyle{ P_{1}^{*}+P_{2}^{*}\overset{?}{=}1 }[/math]即可检验估计概率的归一化。否则,我们得到 [math]\displaystyle{ E\left(P_{Red}\right)+E\left(P_{Black}\right)=\frac{\left(P_{1}^{*}+P_{2}^{*}\right)U\left(Q\right)+\left(2-P_{1}^{*}-P_{2}^{*}\right)U\left(0\right)}{U\left(Q\right)+U\left(0\right)} }[/math]。

于是,现在的问题成了,是否可以假设[math]\displaystyle{ U\left(0\right)=0 }[/math]呢?如果不可以,则我们必须先测量出来[math]\displaystyle{ U\left(Q\right), U\left(0\right) }[/math]才行。这怎么测量呢?

注意,这还是在主观感受概率函数,简称感受概率,[math]\displaystyle{ W\left(x\right)=x }[/math]的条件下的分析。如果我们考虑更加一般的主观概率感受函数,则有 [math]\displaystyle{ U^{EPT}\left(Q,E\left(P_{Red}\right);0,E\left(P_{Black}\right)\right)=\mathcal{E}\left(P_{Red}\right)U\left(Q\right)+\mathcal{E}\left(P_{Black}\right)U\left(0\right)=U^{EPT}\left(Q,P_{1}^{*};0,1-P_{1}^{*}\right)=W\left(P_{1}^{*}\right)U\left(Q\right)+W\left(1-P_{1}^{*}\right)U\left(0\right) }[/math], 以及, [math]\displaystyle{ U^{EPT}\left(0,E\left(P_{Red}\right);Q,E\left(P_{Black}\right)\right)=\mathcal{E}\left(P_{Red}\right)U\left(0\right)+\mathcal{E}\left(P_{Black}\right)U\left(Q\right)=U^{EPT}\left(Q,P_{2}^{*};0,1-P_{2}^{*}\right)=W\left(P_{2}^{*}\right)U\left(Q\right)+W\left(1-P_{2}^{*}\right)U\left(0\right) }[/math]。

于是,得到, [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{E}\left(P_{Red}\right)+\mathcal{E}\left(P_{Black}\right)=\frac{\left(W\left(P_{1}^{*}\right)+W\left(P_{2}^{*}\right)\right)U\left(Q\right)+\left(W\left(1-P_{1}^{*}\right)+W\left(1-P_{2}^{*}\right)\right)U\left(0\right)}{U\left(Q\right)+U\left(0\right)} }[/math]。

如果我们这个时候,希望把主观概率和估计概率分开,则,还需要进一步计算,

[math]\displaystyle{ E\left(P_{Red}\right)+E\left(P_{Black}\right)=W^{-1}\left(\frac{\left(W\left(P_{1}^{*}\right)+W\left(P_{2}^{*}\right)\right)U\left(Q\right)+\left(W\left(1-P_{1}^{*}\right)+W\left(1-P_{2}^{*}\right)\right)U\left(0\right)}{2\left(U\left(Q\right)+U\left(0\right)\right)}+\frac{\left(W\left(P_{1}^{*}\right)-W\left(P_{2}^{*}\right)\right)U\left(Q\right)+\left(W\left(1-P_{1}^{*}\right)-W\left(1-P_{2}^{*}\right)\right)U\left(0\right)}{2\left(U\left(Q\right)-U\left(0\right)\right)}\right) + W^{-1}\left(\frac{\left(W\left(P_{1}^{*}\right)+W\left(P_{2}^{*}\right)\right)U\left(Q\right)+\left(W\left(1-P_{1}^{*}\right)+W\left(1-P_{2}^{*}\right)\right)U\left(0\right)}{2\left(U\left(Q\right)+U\left(0\right)\right)}-\frac{\left(W\left(P_{1}^{*}\right)-W\left(P_{2}^{*}\right)\right)U\left(Q\right)+\left(W\left(1-P_{1}^{*}\right)-W\left(1-P_{2}^{*}\right)\right)U\left(0\right)}{2\left(U\left(Q\right)-U\left(0\right)\right)}\right) }[/math]。

这个表达式是最一般的表达式,当考虑特殊情形,例如[math]\displaystyle{ W\left(x\right)=x }[/math],或者[math]\displaystyle{ U\left(0\right)=0 }[/math]的时候,自然就会回到那些特殊情况下的表达式。尤其是,当[math]\displaystyle{ U\left(0\right)=0 }[/math]的时候,我们得到最简单的表达式 [math]\displaystyle{ E\left(P_{Red}\right)+E\left(P_{Black}\right)=P^{*}_{1}+P^{*}_{2} }[/math],而不用去担心主观感受概率的事情——函数[math]\displaystyle{ W\left(x\right) }[/math]会和其逆函数相互抵消。也就是,我们只需要把测量出来的连个事件对应着的概率加起来,就可以检验估计概率的归一性。

模糊态度实验设计

根据Knight[21],不确定性可以区分为概率已知的风险和概率未知的不确定性,一些学者将概率事件作为基准,将不确定事件与之比较,从而研究模糊态度——不能被明确的概率捕获的那部分不确定的态度(参见Camerer[22]和Trautmann[23]的综述)。

一种检验估计概率是否归一的实验设计是这样的。取一个盒子的混合红球黑球。然后先让被试来比较以下两个行动:行动A——赌如果取出一个球的话取出来的是一个红球来赢取收益Q否则不得钱,行动B——赌概率值为[math]\displaystyle{ P_{1} }[/math]赢取收益Q否则不得钱。尝试各种[math]\displaystyle{ P_{1} }[/math]直到发现A和B没有区别的[math]\displaystyle{ P_{1} }[/math]的值,记做[math]\displaystyle{ P^{*}_{1} }[/math]。接着再让被试来比较以下两个行动:行动A——赌如果取出一个球的话取出来的是一个黑球来赢取收益Q否则不得钱,行动B——赌概率值为[math]\displaystyle{ P_{2} }[/math]赢取收益Q否则不得钱。尝试各种[math]\displaystyle{ P_{2} }[/math]直到发现A和B没有区别的[math]\displaystyle{ P_{2} }[/math]的值,记做[math]\displaystyle{ P^{*}_{2} }[/math]。

然后,检验,[math]\displaystyle{ P^{*}_{1}+P^{*}_{2}\overset{?}{=}1 }[/math]来检验估计概率的归一性。

通过上面的讨论,我们知道,这个实验设计在[math]\displaystyle{ U\left(0\right)=0 }[/math]的条件下是正确的。但是,[math]\displaystyle{ U\left(0\right)=0 }[/math]是合适的选择吗?直接金钱回报的零点是可以随便移动的,但是,效用函数[math]\displaystyle{ E\left(x\right) }[/math]的零点可能不能随便移动。在物理学里面势函数的零点和坐标的零点的改变不改变物理和物理公式的形状,但是,在这里,可能不一样。在物理中,我们进入运动方程的都是势函数的导数项,增加一个常熟不改变任何物理。但是,在经济学问题中,进入决策的可能不是导数项。这时候,怎么办?

一旦[math]\displaystyle{ U\left(0\right)\neq 0 }[/math],我们还需要再考虑主观感受概率函数[math]\displaystyle{ W\left(x\right) }[/math]对估计概率归一性的影响。

模糊实验大多采用人为设计的事件(artificial events)来进行,其中的主观信念可以从对称性假设中推导出来。然而,这样的设置很难运用于自然事件(natural events)。我们无法通过之间观察人们在两个概率不同的自然事件上的选择,来推导人们的模糊偏好,因为人们可能对事件发生的可能性的主观信念是不同的。但是,使用自然事件却可以增加研究的外部有效性[22]。

Baillon等人的自然事件模糊态度的测量

最近,Baillon等人[24]引入了一种新的基于显示偏好的模糊态度测量方法,该方法可以适用于包括自然事件在内的所有事件。这一方法包含2个关键的指数,模糊厌恶(ambiguity aversion)指数(b指数)和模糊感知(ambiguity perception)指数(a指数),后者反映对可能性变化的不敏感性。

模糊考虑的并不是一个单个事件,而是一个分割(a partition),例如,[math]\displaystyle{ \{E,E^c\} }[/math]。假定不确定来源的最低富裕程度,Baillon等人的分割至少存在3个互斥的非空事件[math]\displaystyle{ E_{1},E_{2} }[/math]和[math]\displaystyle{ E_{3} }[/math],例如,股票价格上升大于等于[math]\displaystyle{ 0.05\% }[/math],股票价格下降小于[math]\displaystyle{ -0.1\% }[/math],以及下降不小于[math]\displaystyle{ -0.1\%\lt math/\gt ~上升小于\lt math\gt 0.05\% }[/math]之间。[math]\displaystyle{ E_{ij} }[/math]表示联合[math]\displaystyle{ E_{i} \cup ∪ E_{j} }[/math],其中,[math]\displaystyle{ i \neq j }[/math]。[math]\displaystyle{ E_{i} }[/math]称为一个单个事件(a single event),[math]\displaystyle{ E_{ij} }[/math]称为一个复合事件(a composite event)。然后,利用匹配概率(Matching probabilities),不需要直接地测量,从方程中减出来就能得到b指数和a指数。对于任意的固定价格,比如在他们的实验中,€20,通过以下的无差异定义事件E的匹配概率[math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math]:

在事件E下收到€20等价于以概率[math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math]收到€20。————————(1)

在模糊中性的条件下,一个事件,比如[math]\displaystyle{ E_{1} }[/math]的概率[math]\displaystyle{ m(E_{1}) }[/math],和它的互补事件[math]\displaystyle{ E_{2,3} }[/math]的概率[math]\displaystyle{ m(E_{2,3}) }[/math]之和等于1,如果是模糊厌恶的,则和小于1,如果是模糊喜好的,则大于1。记[math]\displaystyle{ m_i=m(E_{i}) }[/math],[math]\displaystyle{ m_{i,j}=m(E_{i,j}) }[/math],单个事件平均的匹配概率为[math]\displaystyle{ \overline m_s=(m_1+m_2+m_3)/3 }[/math],复合事件平均的匹配概率为[math]\displaystyle{ \overline m_c=(m_{2,3}+m_{1,3}+m_{1,2})/3 }[/math],定义:

模糊厌恶指数(ambiguity aversion index)是:

[math]\displaystyle{ b=1-\overline m_s-\overline m_c }[/math].——————————————————(2)

[math]\displaystyle{ b=0 }[/math],表示模糊中性,即对平均单个事件和互补的复合事件的概率和为1;[math]\displaystyle{ b\lt 0 }[/math],表示模糊喜好,[math]\displaystyle{ b\gt 0 }[/math],表示模糊厌恶。[math]\displaystyle{ b }[/math]的最大值为1,即,所有事件的概率都为0,极度模糊厌恶,最小值为[math]\displaystyle{ -1 }[/math],即,所有事件的概率都为1,极度模糊喜好。

模糊不敏感指数(The ambiguity-generated insensitivity (a-insensitivity) index)是:

[math]\displaystyle{ a=3 \times \left( 1/3-\left(\overline m_c-\overline m_s \right)\right) }[/math].———————————————(3)

[math]\displaystyle{ a }[/math]指数反映的是所有事件的概率都退回到一半一半(fifty-fifty)的程度。如果所有事件的匹配概率都是1/2,或者,单个事件的平均匹配概率与复合事件的匹配概率都是1/2,那么,[math]\displaystyle{ a=1 }[/math],这可以看作是完全模糊的情况(不过,根据公式,并不能排除[math]\displaystyle{ a\gt 1 }[/math],也就是说,单个事件的平均概率大于复合事件的平均概率)。另一方面,如果平均而言,单个事件的匹配概率是1/3而复合事件的匹配概率是2/3,那么,[math]\displaystyle{ a=0 }[/math],这看来是不模糊的。

结合确定性等价实验

为了测量出来[math]\displaystyle{ U\left(0\right) }[/math],或者说[math]\displaystyle{ U\left(0\right) }[/math]和[math]\displaystyle{ U\left(Q\right) }[/math]的关系——只有要这个关系我们就可以把上面那个一般公式计算出来,我们引入确定性等价。

如果我们找到了[math]\displaystyle{ U^{EPT}\left(Q, P_{1}; 0, 1-P_{1}\right) }[/math]的确定性等价[math]\displaystyle{ U^{EPT}\left(S,1; 0, 0\right) }[/math],则,

[math]\displaystyle{ U^{EPT}\left(Q, P_{1}; 0, 1-P_{1}\right)=W\left(P_{1}\right)U\left(Q\right)+W\left(1-P_{1}\right)U\left(0\right)=W\left(1\right)U\left(S\right)+W\left(0\right)U\left(0\right)=U^{EPT}\left(S,1; 0, 0\right) }[/math],也就是 [math]\displaystyle{ U\left(0\right)=\frac{W\left(P_{1}\right)U\left(Q\right)-W\left(1\right)U\left(S\right)}{W\left(0\right)-W\left(1-P_{1}\right)} }[/math]。

对于[math]\displaystyle{ W\left(x\right)=x }[/math]的特殊情况,[math]\displaystyle{ U\left(0\right)=\frac{U\left(S\right)-P_{1}U\left(Q\right)}{1-P_{1}} }[/math]。由于函数[math]\displaystyle{ U\left(x\right) }[/math]未知,这个实验还是不能完全解决发现[math]\displaystyle{ U\left(0\right) }[/math]的值的问题。

当然,如果没有未给出来的概率,也就是所有的概率都是已知的,则函数[math]\displaystyle{ E\left(p\right)=p }[/math],我们就回到了带有主观概率的期望效用理论,也就是之前讨论的情景了。

当然,这一节的讨论是在承认用前景理论来描述带有随机性的决策的效用函数的前提下做的。而我们更大的角度的工作是考虑一旦放弃这个用前景理论来描述随机性决策的前提,会如何,理论应该长成什么样。例如[math]\displaystyle{ U=U\left(E\left(\rho\right),\Delta\left(\rho\right),\eta\left(\rho\right),\cdots \right) }[/math]。

为什么不能直接定义效用零点为[math]\displaystyle{ U\left(0\right)=0 }[/math]?

在物理学的势函数里面,势能的零点是可以任意选择的,只要确定好就可以。运动方程不随着这个零点的改变而改变(势函数的导数才进入运动方程)。同时,坐标变量的零点也是可以任意选择的,运动方程也不随着坐标原点的选择而改变。但是,在经济学问题里面,按照前景理论,货币收益取值的零点就不是能够任意选择的,[math]\displaystyle{ U\left(x\right) }[/math]不是平移不变的,也就是[math]\displaystyle{ U\left(x-y\right)=U\left(x\right)-U\left(y\right) }[/math]。也就是说,首先坐标原点就不是任意取值的。

另外,在经济学里面,一旦考虑主观估计概率,效用函数的零点也不是能够任意选择的。我们来试着给效用函数添加一个常数,也就是 [math]\displaystyle{ E\left(P_{Red}\right)\left(U\left(Q\right)+U_{0}\right)+E\left(P_{Black}\right)\left(U\left(0\right)+U_{0}\right)=P_{1}^{*}\left(U\left(Q\right)+U_{0}\right)+\left(1-P_{1}^{*}\right)\left(U\left(0\right)+U_{0}\right) }[/math],得到[math]\displaystyle{ E\left(P_{Red}\right)U\left(Q\right)+E\left(P_{Black}\right)U\left(0\right)+\left(E\left(P_{Red}\right)+E\left(P_{Black}\right)\right)U_{0}=P_{1}^{*}U\left(Q\right)+\left(1-P_{1}^{*}\right)U\left(0\right)+U_{0} }[/math]。

如果我们有[math]\displaystyle{ E\left(P_{Red}\right)+E\left(P_{Black}\right)=1 }[/math],则自然就会回到没有[math]\displaystyle{ U_{0} }[/math]的表达式,也就是,[math]\displaystyle{ E\left(P_{Red}\right)U\left(Q\right)+E\left(P_{Black}\right)U\left(0\right)=P_{1}^{*}U\left(Q\right)+\left(1-P_{1}^{*}\right)U\left(0\right) }[/math]。

但是,这里的问题就是检验[math]\displaystyle{ E\left(P_{Red}\right)+E\left(P_{Black}\right) }[/math]是否等于1,因此,实际上,一旦考虑这个主观估计概率,我们的效用函数零点就不能随便取。

既然不能随便取,那怎么办?

实际上,在前景理论中,如果面对的选择是两个不同的概率取值不同收益取值的彩票,也会出现这个效用函数零点不能随便取的问题。比如说,[math]\displaystyle{ U^{PT}\left(P_{1}, Q_{11}; 1-P_{1}, Q_{12}\right)=U^{PT}\left(P_{2}, Q_{21}; 1-P_{2}, Q_{22}\right) }[/math],得到[math]\displaystyle{ W\left(P_{1}\right)U\left(Q_{11}\right)+W\left(1-P_{1}\right)U\left(Q_{12}\right)=W\left(P_{2}\right)U\left(Q_{21}\right)+W\left(1-P_{2}\right)U\left(Q_{22}\right) }[/math],如果给效用函数增加一个常数[math]\displaystyle{ U_{0} }[/math],则只有下式成立的时候方程才相同, [math]\displaystyle{ W\left(P_{1}\right)+W\left(1-P_{1}\right)=W\left(P_{2}\right)+W\left(1-P_{2}\right) }[/math]。但是,这个等式成立吗?这个问题相当于是问,主观感受概率函数[math]\displaystyle{ W\left(x\right) }[/math]是否满足归一性。有相关研究吗?设计一个实验来研究一下?如果主观感受概率没有归一性,则在前景理论中,同样效用函数的零点不能任意选择。实际上,现在看起来,前景理论给出来的[math]\displaystyle{ W\left(x\right) }[/math]不满足归一性[10]。

[math]\displaystyle{ W\left(P_{1}\right)+W\left(1-P_{1}\right)\overset{?}{=}1 }[/math]的问题

实际上,这个[math]\displaystyle{ W\left(P_{1}\right)+W\left(1-P_{1}\right)\overset{?}{=}1 }[/math]的问题本身就是一个很有意思的问题。考虑下面一种情形,我们取[math]\displaystyle{ Q_{1} }[/math]越来越接近于[math]\displaystyle{ Q_{2} }[/math]。当我们的[math]\displaystyle{ Q_{1}=Q_{2}=Q }[/math]的时候,实际上,这是一个确定性问题,于是,效用应该是[math]\displaystyle{ U\left(P_{1}, Q; 1-P_{1}, Q\right)=W\left(1\right)U\left(Q\right)=W\left(P_{1}\right)U\left(Q\right)+W\left(1-P_{1}\right)U\left(Q\right) }[/math],于是得到,[math]\displaystyle{ 1=W\left(1\right)=W\left(P_{1}\right)+W\left(1-P_{1}\right) }[/math]。其中我们用到了[math]\displaystyle{ 1=W\left(1\right) }[/math](相应地[math]\displaystyle{ 0=W\left(0\right) }[/math])。可是,这个条件明明不满足啊。这是这个理论本身的一个问题,内部不自洽。或者说,这个理论在[math]\displaystyle{ Q_{1} }[/math]越来越接近于[math]\displaystyle{ Q_{2} }[/math]的时候,有一个突变:用[math]\displaystyle{ U\left(P_{1}, Q_{1}; 1-P_{1}, Q_{2}\right)=W\left(P_{1}\right)U\left(Q_{1}\right)+W\left(1-P_{1}\right)U\left(Q_{2}\right) }[/math]描述不同的[math]\displaystyle{ Q_{1} }[/math]和[math]\displaystyle{ Q_{2} }[/math]是可以的,但是,一旦遇到[math]\displaystyle{ Q_{1}=Q_{2} }[/math],则这个效用函数不能用。或者说,实际上,函数关系是这样的,[math]\displaystyle{ U\left(P_{1}, Q_{1}; 1-P_{1}, Q_{2}\right)=W\left(P_{1}, Q_{1}, Q_{2}\right)U\left(Q_{1}\right)+W\left(1-P_{1}, Q_{1}, Q_{2}\right)U\left(Q_{2}\right) }[/math]。

也就是说,如果我们通过实验确实验证了[math]\displaystyle{ W\left(P_{1}\right)+W\left(1-P_{1}\right)\neq 1 }[/math],那么,就证明了[math]\displaystyle{ U\left(P_{1}, Q_{1}; 1-P_{1}, Q_{2}\right)=W\left(P_{1}\right)U\left(Q_{1}\right)+W\left(1-P_{1}\right)U\left(Q_{2}\right) }[/math]是不对的。

另一方面,这个问题还和上面提到的模糊态度有关:在面对一个接近真实的带随机性的决策情景的中,一般来说,我们要面对的决策是对概率情景的一种估价,而不是直接对这个情景背后的概率做一个估计;这个时候就会存在两种可能的模糊态度——由于需要对概率估计带来的模糊,以及在得到明确的概率之后,主观概率感受带来的模糊。也就是说,实际上,有两件事情需要检验:[math]\displaystyle{ W\left(E\left(P_{1}\right)\right)+W\left(E\left(1-P_{1}\right)\right)\overset{?}{=}1 }[/math],[math]\displaystyle{ W\left(P_{1}\right)+W\left(1-P_{1}\right)\overset{?}{=}1 }[/math],或者说完全分开成两个因素:[math]\displaystyle{ E\left(P_{1}\right)+E\left(1-P_{1}\right)\overset{?}{=}1 }[/math],[math]\displaystyle{ W\left(P_{1}\right)+W\left(1-P_{1}\right)\overset{?}{=}1 }[/math]。当然,[math]\displaystyle{ P_{1}+1-P_{1}=1 }[/math]不用检验。

如果说[math]\displaystyle{ W\left(P_{1}\right)+W\left(1-P_{1}\right)\neq 1 }[/math],那么就算[math]\displaystyle{ E\left(P_{1}\right)+E\left(1-P_{1}\right)=1 }[/math],我们仍然可能有[math]\displaystyle{ W\left(E\left(P_{1}\right)\right)+W\left(E\left(1-P_{1}\right)\right)\neq 1 }[/math]。当然,三者都不等于1的情况也是可能出现的。

另外,[math]\displaystyle{ W\left(E\left(P_{1}\right)\right)+W\left(E\left(1-P_{1}\right)\right)\overset{?}{=}1 }[/math]不能直接检验,除非我们知道了效用函数的函数形式[math]\displaystyle{ U\left(x\right) }[/math]。当然,这也不是就不能知道。见[10]。

于是,如果我们检验了[math]\displaystyle{ W\left(P_{1}\right)+W\left(1-P_{1}\right)\overset{?}{=}1 }[/math],我们还可以知道更多关于模糊态度的根源的问题。

具体如何检验[math]\displaystyle{ W\left(P_{1}\right)+W\left(1-P_{1}\right)\overset{?}{=}1 }[/math]?

方法可以是针对给定的彩票来选择相配的收益。也就是,例如,对于如下彩票:以概率[math]\displaystyle{ P_{1} }[/math]获得[math]\displaystyle{ Q_{1} }[/math]收益,以概率[math]\displaystyle{ 1-P_{1} }[/math]获得[math]\displaystyle{ Q_{2} }[/math]收益,选出来一个确定性等价的收益值[math]\displaystyle{ Q }[/math]。然后在[math]\displaystyle{ Q_{1} }[/math]不断接近[math]\displaystyle{ Q_{2} }[/math]的情况下来看所选择的等价的确定性收益[math]\displaystyle{ Q }[/math]。如果[math]\displaystyle{ W\left(P_{1}\right)+W\left(1-P_{1}\right)=1 }[/math],则[math]\displaystyle{ Q_{1}=Q_{2}=Q }[/math]。

当然,如果效用函数[math]\displaystyle{ Q\left(x\right) }[/math]已知,则一般的[math]\displaystyle{ Q_{1} }[/math]和[math]\displaystyle{ Q_{2} }[/math]的实验结果,也可以用来检验上式。

参考文献

- ↑ Holt, C. A., & Laury, S. K. (2002). Risk aversion and incentive effects. American Economic Review, 92(5), 1644-1655. http://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/3083270.pdf

- ↑ Laury, S. K., & Holt, C. A. (2008). Further reflections on the reflection effect, in James C. Cox, Glenn W. Harrison (ed.) Risk Aversion in Experiments (Research in Experimental Economics, Volume 12) Emerald Group Publishing Limited, pp.405 - 440. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0193-2306(08)00009-4

- ↑ Gary Charness, Uri Gneezy and Alex Imas, Experimental methods: Eliciting risk preferences, Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 87(2013), 43-51, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2012.12.023.

- ↑ Dave C, Eckel C C, Johnson C A, et al. Eliciting risk preferences: When is simple better?[J]. Journal of Risk & Uncertainty, 2010, 41(3):219-243. http://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/41761450.pdf

- ↑ Habib, S., Friedman, D., Crockett, S. et al. J Econ Sci Assoc (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40881-016-0032-8.

- ↑ Neumann J L V, Morgenstern O V. (1944) The Theory of Games and Economic Behavior. Princeton University Press.

- ↑ Friedman M, Savage L J. (1948) The Utility Analysis of Choices Involving Risk[J]. Journal of Political Economy, 56(4):279-304. http://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/1826045.pdf

- ↑ Kahneman, Daniel, Tversky, Amos (1979). "Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk". Econometrica: Journal of the econometric society. 47 (2): 263–291.https://www.jstor.org/stable/1914185

- ↑ Quiggin J. (1982) A theory of anticipated utility[J]. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 3(4):323-343.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Tversky A, Kahneman D. (1992) Advances in prospect theory: Cumulative representation of uncertainty[J]. Journal of Risk & Uncertainty, 5(4):297-323. http://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/41755005.pdf

- ↑ Bowman D, Minehart D, Rabin M. (1999). Loss aversion in a consumption–savings model[J]. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 38(2):155-178.

- ↑ Kőszegi B, Rabin M. (2006). A Model of Reference-Dependent Preferences[J]. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 121(4):1133-1165. http://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/25098823.pdf

- ↑ Schmidt U, Starmer C, Sugden R. (2008). Third-generation prospect theory[J]. Journal of Risk & Uncertainty, 36(3):203. http://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/41761341.pdf

- ↑ Harbaugh, William T., et al. (2010) “The Fourfold Pattern of Risk Attitudes in Choice and Pricing tasks.” The Economic Journal, vol. 120, no. 545, 2010, pp. 595–611. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/40784579.pdf

- ↑ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prospect_theory

- ↑ Markowitz H. (1952) Portfolio Selection[J]. Journal of Finance, 7(1):77-91. http://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/2975974.pdf

- ↑ J. Tobin. (1858) Liquidity Preference as Behavior Towards Risk, The Review of Economic Studies, Volume 25, Issue 2, Pages 65–86, https://doi.org/10.2307/2296205

- ↑ Levy H, Levy M. Prospect Theory and Mean-Variance Analysis[J]. Review of Financial Studies, 2004, 17(4):1015-1041. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/3598057.pdf

- ↑ Savage, L. (1954). The Foundations of Statistics.[M]. JOHN WILEY.

- ↑ Ellsberg, D. (1961). Risk, Ambiguity, and the Savage Axioms. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol. 75, no. 4, 1961, pp. 643–669. http://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/1884324.pdf

- ↑ Knight F.H. (1921) Risk, uncertainty and profit[M].Mineola, New York:Dover Publications, InC.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 CAMERER, C., & WEBER, M. (1992). Recent Developments in Modeling Preferences: Uncertainty and Ambiguity. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 5(4), 325-370. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41755006

- ↑ Trautmann, Stefan T., and Gijs Van De Kuilen. (2015) "Ambiguity attitudes." The Wiley Blackwell handbook of judgment and decision making 1: 89-116.

- ↑ Baillon, A., Huang, Z., Selim, A., Wakker, P. (2018). Measuring Ambiguity Attitudes for All (Natural) Events. Econometica, forthcoming. http://www.lingnan.sysu.edu.cn/UploadFiles/xsbg/2017/3/201703271008320149.pdf

这是这个页面的英文版 (There is a English version of this page):Measurement_of_risk_attitude。

本分类目前不含有任何页面或媒体文件。